法王新闻 | 2022年04月

『第7届谶摩春季』噶玛巴米觉多杰自传•第十天第一堂课

『7th Arya Kshema』AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL VERSES OF KARMAPA MIKYÖ DORJE• The 1st Session of Day 10

རྗེ་བཙུན་མི་བསྐྱོད་རྡོ་རྗེའི་རྣམ་ཐར། བདེ་བྱེད་མའི་དཔྱིད་ཆོས། ཉིན་བཅུ་པ།།

時間:2022年04月09日 09th April, 2022 21:00-22:00(北京时间)

Uploaded on 2022.04.15

Last updated on 2023.04.05

修行不是外相上的

Authentic Dharma Practice

大家都听得到吗?

那么透过网路观看的我们说的“皈依处”,尤其是尼众们,还有所有的善知识们,各地的法友们,所有的朋友们,大家身体健康,大家好! 今天是谶摩春季课程的第10天、第10堂课。我们这次春季的课程大概会讲到第20还是21个颂文,讲到第21个偈文。(Bamboo:事实上只讲到第20个偈文,后面有一堂课被替换成假的了。) 所以,还剩下3个颂文,也是课程接近尾声了。

从22个颂文开始到之后,我们会从明年开始讲,应该明年就可以讲完。再后年要讲什么样的内容,再听听大家讨论之后的意见,我再做一个决定。今天要跟各位讲的就是,法王 《妙行解脱自传》当中的第18个颂文。

依据法王米觉多杰的侍者,也是他的弟子——桑杰巴珠所写的《妙行解脱传》的注解中的科判来看的话,观修世俗菩提心的部分有分为“座上”和“座下”。

The Karmapa continued his discussion of the second part of the passage about meditating on relative bodhichitta according to Sangye Paldrup's commentary: Taking adversity as the path in post-meditation.

“座下:转恶缘为道用”总共有10个,前面七个部分我们都已经讲过了。今天要讲的是第8个:转兴衰为道用。

This section has ten sub-topics and today's teaching began with the eighth sub-topic: Taking things going well or badly as the path.

8. འབྱོར་རྒུད་ལམ་ཁྱེར།

Taking things going well or badly as the path

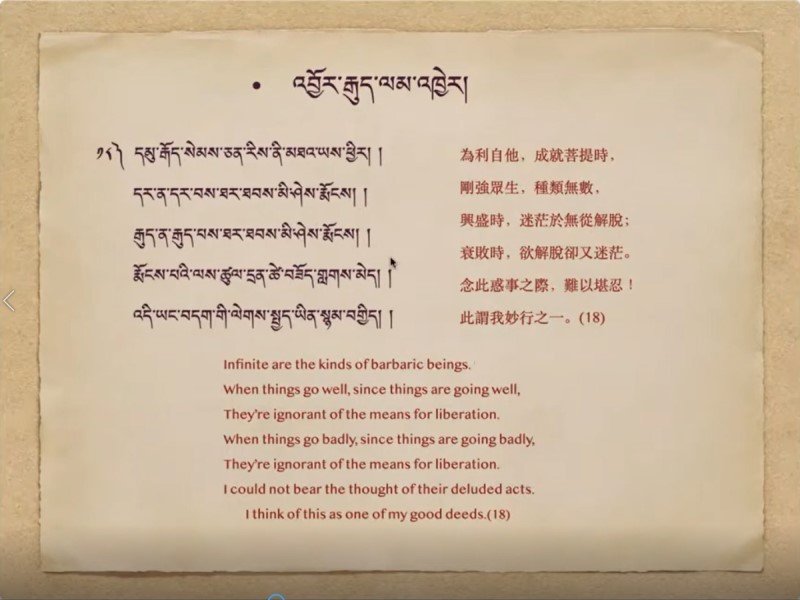

转兴衰为道用༡༨༽ དམུ་རྒོད་སེམས་ཅན་རིས་ནི་མཐའ་ཡས་ཕྱིར། ། དར་ན་དར་བས་ཐར་ཐབས་མི་ཤེས་རྨོངས། ། རྒུད་ན་རྒུད་པས་ཐར་ཐབས་མི་ཤེས་རྨོོངས། ། རྨོངས་པའི་ལས་ཚུལ་དྲན་ཚེ་བཟོད་གླགས་མེད། ། འདི་ཡང་བདག་གི་ལེགས་སྤྱད་ཡིན་སྙམ་བགྱིད། །

Infinite are the kinds of barbaric beings. When things go well, since things are going well, They’re ignorant of the means for liberation. When things go badly, since things are going badly, They’re ignorant of the means for liberation. I could not bear the thought of their deluded acts. I think of this as one of my good deeds.(18)

剛強眾生,種類無數,興盛時,迷茫於無從解脫;衰敗時,欲解脫卻又迷茫。念此惑事之際,難以堪忍!此謂我妙行之一。(18)

所谓的“大德”都是法油子

法王米觉多杰的时代,大部分的人都没有什么知识,也不太会思考,心性都是比较顽劣的。大部分都是这样的人。其中很多人是说“弘扬佛法”的人,而且是受到他人景仰和信仰的这样一些大德。

他们可能也很有名。虽然是这样子,但是当他们遇到自己兴盛的时候,或者当自己这一边的人兴盛的时候,他们还想得到更多,变得更兴盛。譬如说得到更多的僧人;寺院不够大,还要更大。结果就

没日没夜地沉溺在这样的贪著当中。由于这样的一种散乱,让他们都变成一种“法油子”——‘心’和‘法’完全没有办法相应。

During Mikyö Dorje's lifetime, the Karmapa explained, most people were uneducated. They hadn't been trained how to think. Their mindstreams were

untamed and they were rough and often incorrigible, so it was difficult to change them. They included some "people who upheld, protected, and spread

the teachings", people in whom others placed their hopes, some of whom "were given lofty names". When things went well for them and their group,

they had everything they needed and weren't concerned that there were few monks in the monasteries. Their work for their monasteries kept them busy

day and night and acted as a distraction. Consequently, their characters became intractable and rigid, so it was extremely difficult for them to mix

their mindstreams with the dharma.

Bamboo评论:大宝七岁坐床,弘法了三十年,大概是唯一一个没有属于他的寺庙,也没有一个他养的僧人或弟子。甚至没有任何他名下的不动产和动产,他住锡在上密院时,平时出入坐的车, 别人都强调这是法王办公室的财物,不是大宝法王的财产。长期住锡的是格鲁派的寺庙;主管他一切财物和行程的噶玛巴办公室的头头是宁玛派的竹庆本乐仁波切;中文官网是萨迦派的宗萨仁波切的弟子在管理和经营; 其他的打着他名头的什么“正法电子书(dharmaebooks.org)”等网站的经营者都是创古老妖的人。所以“出家戒”最重要一条“不捉持金钱戒”,他的确持守得古往今来独步天下。

为什么要弄成这样呢?他刚到印度时,噶玛巴办公室是由大司徒仁波切的总管掌管的,之后就突然死了;建噶举祈愿会场时,大司徒仁波切的大施主,“内燃”家族的人倾尽全力地帮忙,结果也突然死了; 和不顾封禁坚持要来见大宝的波卡仁波切也突然死了;大宝坐床的鼎立支持者——英国籍的阿贡仁波切也突然在西藏被杀了。

大宝后来就选了宁玛派的竹庆本乐仁波切来掌管自己的办公室,竹庆本乐仁波切是宁玛派,又是美国籍, 达赖集团不敢杀;台湾中文网的经营者是萨迦派的宗萨仁波切的人,宗萨仁波切是不丹人,不想得罪不丹,达赖集团不敢动台湾中文网;控制锡金十六世噶玛巴几个法座的国师嘉察仁波切有锡金的鼎立支持,况且从小 无依无靠的嘉察仁波切也是创古老妖选中,里应外合一起早早送十六世上西天的合作伙伴,所以达赖和中共都对他很放心;创古老妖嘛,即是达赖的人,又有土共的支持,达赖集团当然不会动,也不敢动。大司徒仁波切早早入了印度籍,没有任何政治靠山, 所以,他的人达赖集团就根本不必顾忌,这和波卡仁波切是一样的。阿贡仁波切是英国籍,在西藏被杀后,英国这边竟然还呼吁不要追究杀人者,所以这种半路换国籍的是最没靠山的。靠山也不一定是哪国政府、权贵,和你同宗同籍、同语言、同文化的老百姓也是啊。

另外一种情况是,当自己和当自己这边的人,当自己这边的很多事情都衰败的时候,这时候他们一心想的就是:如何赶快地再兴盛起来。总之,想尽办法、

胡思乱想地想着要再兴盛起来。所以,根本就没有人,也没有心思去想“怎么解脱和成佛”。所以很少人在想“怎么解脱”跟“成佛”。任何其他时候,也不是特别兴盛,

或衰败,就是平常的时候。只要有一点空闲,他们想的是什么呢?就是吃喝,要么就是睡觉,要么就是发懒、懒散,就是这样子而已。他们也不会想到佛法上,

好好修行。(Bamboo之前就是这样的,能躺着就不想坐着。要不是被现实打得屁滚尿流,前途事业一帆风顺的话,是根本不会想到佛法的。)

When things went badly for them and their group, they did everything they could to restore what they had lost. They were so distracted by their thoughts and busyness

that they had no time to think about the means to achieve liberation and omniscience, nor were there many people who knew the path to liberation. When people had

leisure time, they would relax and enjoy the pleasures of food, drink, sleep, and lolling about—very few thought about practising the dharma.

米觉多杰的“耍猴”开示

所以法王米觉多杰只要想到这些末法、浊世的众生顽劣的行为,就会生气,难忍的大悲。当时,米觉多杰平常会见很多的人,这些来觐见法王的人,法王都会很详细

地询问他们,譬如说,你的年纪?也会询问他们:你们在做些什么?这个月或这几年当中,你们做了些什么?等等。这些人也会很详细地跟法王做报告。

当法王从他们的回话中得知,他们很没有意义地浪费了宝贵的生命的时候,就会感到非常地担忧,直接针对他们做一些开示。甚至会说:“你有没有感觉到,甚至闻到你

口中跟鼻子,你有没有闻到一种臭味?你有没有闻到你嘴巴里,跟鼻子里有一种臭味?一种腐败掉的臭味。”见他的人就会说:“没有闻到。”米觉多杰接着会说:“

真是太奇特了,你整个里面都腐烂掉了,就是你的整个身体里面都腐烂掉了。你竟然还没有闻到这样的臭味?!真是太奇特了。你自己都没闻到这个臭味。”所以这是法王直接的一种开示。

意思就是“一生都被你浪费掉了,完全浪费掉了。”就算你有这样的心智,但是也没有好好用。所以他会说出很多这种很重要、直接的话。

When people came to see him, Mikyö Dorje would invariably ask questions in great detail about how old they were and what they had been doing. He

grew immensely concerned when it seemed from their replies that they were wasting their lives. He would speak to them very directly with words that

hit the mark. The Karmapa gave an example. Mikyö Dorje would ask, "Do you smell the scent of rot in your nose or mouth?" The students would be surprised

and reply that they did not. Mikyö Dorje would say, "That’s really amazing! Everything inside you has rotted, and you don’t even smell it. That’s really strange.”

He was pointing out to them very clearly that they had wasted the facilities of their human life.

Bamboo评论:以前我母亲坐在电脑前看股票,Bamboo如果站她身边说话,她每次都会莫名其妙的坐立不安,说“你身上有股臭味。”Bamboo很奇怪,用手捂住嘴,使劲哈了口气,再用鼻子闻闻,不觉得有口臭啊!就问她哪里臭, 她也说不出来,就是说你臭。所以米觉多杰就跟Bamboo母亲一样,神经质的很。就跟大宝前面说的,这些来听他开示的人“的确没什么知识,不太会思考。”想听这种开示,去精神病院好了,里面这种大师多得很。

还有很多人会跟法王请法,法王也会说得很直接,话都说得蛮重的。法王会对这些请法的人说,

Many people would come to ask for dharma teachings. He would admonish them:

Years, months, and days have gone by already. You are getting closer and closer to death. Likewise, this body, composed of the four elements, is changing. You used to be youthful, but now you are getting old and bent. Your close friends haven’t been of much help, other than fooling you, and up until now, you’ve only been focused on this lifetime. You haven’t thought about your future lives. You have come under the control of these negative friends who won’t bring you to the way of virtue. You have been distracted and deceived by temporary needs. Even if you only have a little wealth, you become really attached to it, and this prevents you from working for the benefit of others. Even when you’re practising dharma, you’re unable to stand; it’s as if you have lost all your control to the Maras. 大一点来说,你被寺院跟弟子绑住了;说小一点,你也就是被某几个施主给绑住了。最后呢,是你自己把你自己的福给折光了。像你这样的人,是不是被称为一个叫修行者? 或者遁世的隐士的修行者?有没有这样的名称还有什么差别呢?”

It was as if these people were trapped in quicksand; their dharma practice was questionable and they were under the control of their sponsors, the Karmapa commented. They might have accumulated some merit previously, but now they were losing it, and though they might be called “dharma practitioners” or “renunciates”, this was actually not true. 接下来想讲一下这个颂文里有几个重点。我觉得它可以有三个重点。

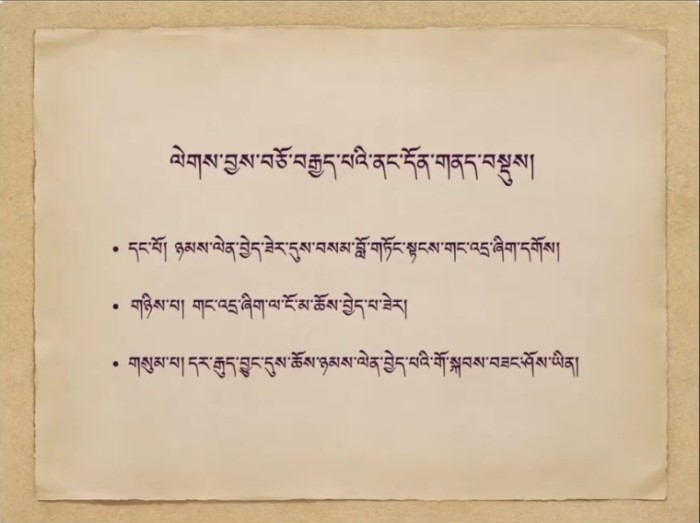

There are three main aspects to the eighteenth good deed:

ལེགས་བྱས་བཅོ་བརྒྱད་པའི་ནང་དོན་གནད་བསྡུས།

The main aspects of the 18th good deed

第18个颂文的重点དང་པོ། ཉམས་ལེན་བྱེད་ཟེར་དུས་བསམ་བློ་གཏོང་སྟངས་གང་འདྲ་ཞིག་དགོས།

The understanding and way of thinking necessary for practice.

一、应该要如何理解和看待所谓的修行;གཉིས་པ། གང་འདྲ་ཞིག་ལ་ངོ་མ་ཆོས་བྱེད་པ་ཟེར།

What practising dharma really means.

二、怎么样才是做到真正的修法;གསུམ་པ། དར་རྒུད་བྱུང་དུས་ཆོས་ཉམས་ལེན་བྱེད་པའི་གོ་སྐབས་བཟང་ཤོས་ཡིན།

The best opportunities for practice are when things are going well or badly.

三、在你大起大落时,才是你修行最好的时机。

I 什么才是修行

The understanding and way of thinking necessary for practice.

第一个就是你如何理解和看待修行。我觉得这是要非常清楚的。在这几天当中,我们简单地说明过了,有关“什么是修行”这样的内容。但是,可能还是有很多人听完之后会觉得,谈到了修行,

你心中想到的是什么呢?修行,你觉得是“念经”;或者修行,你想到的就是“修法”;或者“持咒”;或者“放生”等等这些。平常我们想到“修行”的时候,可能心中会出现的一些画面,

要念经、修法、持咒、放生这些你觉得就是“修行”。甚至有些人,当你想到修行的时候,可能会觉得“修行”就只有在佛堂里面,发生在佛堂里面的,才叫做“修行”。或者,不见得是特别的空间,

而是只要有佛像的地方,或者你坐在蒲团上的时候,那才算是所谓的修行。

Many people continue to think that practice means reciting prayers, offering pujas, reciting mantras, life releases, and so forth. Moreover, people

often believe that practice only happens in the shrine room or sitting in front of the household shrine.

譬如说,你到了一个人家的时候,你没见到父亲在哪,你问小孩:“爸爸在哪里?”小孩就说:“爸爸在佛堂,在修行。”小孩为什么会说:“爸爸在修行?” 因为爸爸在佛堂里面,所以你就觉得他在修行,因为他在那个空间,你就觉得他在修行,就是那个感觉。

当然,念经、修法、放生、持咒,这些是修行。

但只是这个样子,我们认为这就是修行的话;只有这些才是修行;或者只有在佛堂里面才是修行;或者只有在蒲团上等等这些才是修行的话;或者只有念经、只有修法、只有持咒这些才是修行

的话,这样对于什么是修行还是不是真实的了解。譬如说,你口头可能在念经,但你心中可能还是烦恼,想着轮回中的,这还是不行的。所以,真正的修行是超越了外相,它是更深刻一些的。(Bamboo: 想起《道德经》的‘道可道,非常道’。)

Of course, the Karmapa clarified, reciting prayers, pujas and life release are part of dharma practice, but if you think that they are the sum of dharma

practice, you have misunderstood.Practising the dharma goes much deeper and should not be confused with the external appearances of practice. While you

are reciting prayers, your mind can be elsewhere and you might be harbouring a myriad of thoughts. Truly practising dharma is far more profound.

还有一些人可能会觉得修行是什么呢?就是修行必须是

很正规、很严肃、很正式的一件事情;还有一些人会觉得修行是蛮无聊的,蛮枯燥乏味的一件事情。总之,很多人并不是很了解修行,他们想到修行,就会觉得修行会蛮枯燥、乏味的。对他们来讲,修行

就是:我要修行了!好像要开始读一本很艰涩的、学术的书是一样的,他们会觉得很累。或是要读一本很深的历史书籍。或者是要开始学习某一门学科,

譬如说,数学吧。很多僧众你们可能没有特别学过数学。对很多人来讲,修行就好像要学这样一门烧脑的、很用脑的学科是一样的。总之觉得修行是需要很正经八百、很花时间的一个事情。很多人觉得

修行就会很幸苦、很累。要专心、要观想,要做很多事情,很多人就会觉得这太困难了。

Some people think of dharma practice as a high-level activity and approach it as if it were similar to work, demanding application and meticulousness.

Others believe that dharma practice is boring and have little interest in it. Some see practising dharma as very complicated and difficult activity that

can be both challenging and boring, like having to read an old, historical document, so it’s difficult to be enthusiastic. Alternatively, they think it’s

like studying mathematics which can be extremely demanding, so you have to work really hard and think hard—you have to meditate and focus on complicated

visualisations. All these misconceptions put many people off practising dharma.

或者有些人稍微开始想修了,但他就会觉得要准备好,才要开始修,所以他什么都要准备好,心情要准备好,甚至房间的温度都要准备好,像印度太热就不行,但太冷也不行,不能让自己太冷。

首先要把房间的温度准备好,要调好;然后心情也要放轻松;但这还不够,在这之前还有很多其他事情要先做好。还有什么事要做好?譬如说微信什么该回的、该看的先把它看完,

该划的、该刷的,该看的脸书也好,微信也好,该处理完的处理完;该回的简讯信息也回了;饭也吃饱了;睡也睡饱了,什么都处理好了,准备好了,终于有空闲了,然后才坐在蒲团上说:“

我可以开始修行。”反正就觉得“修行”不是个必须的事情,其它的反而比较重要。总之,最重要的其它那些得先处理好,最后最后剩那一点点时间,“好吧,好好修行,赶快做一做。”

就这个感觉。那些得先忙完,最后最后才是做修行,附带地做一下修行,这种感觉。然后,开始修行了,他要干嘛呢?修行对他来说,是个很有仪式感、很正式的、很严肃的,好像是一份工作,或者

一个任务你要去完成,就是你必须要刻意去完成的、被迫去完成的,很有仪式感、很严肃的这样一个工作或任务。

Then there are some people who say they want to practice the dharma but they need perfect conditions in order to practice. They need to feel comfortable;

it mustn’t be too hot, like in India sometimes, or too cold. However, before they can begin, there’s a lot of work to be done. They need to check all their

WhatsApp or WeChat messages, and their Facebook, count the number of ‘likes’, and write replies. Then, they must also eat because their stomachs have to be

full. Basically, after everything that needs to be done has been done, when they have a little bit of free time, only then do they sit down on their meditation

cushion and try to do a little dharma practice. It seems as if they lead really busy lives, when, in fact, they are not doing much of value. Yet, they never

have time to practice the dharma.

仲敦巴和阿底峡的“师心我心合一无别”

这里,我就想到有一个故事,没什么故事特别好说,大部分故事都说完了。这个故事可能你们听过了,不是一个很长的故事。

There are several faults to seeing dharma practice in this way, the Karmapa warned, and illustrated his point with two stories.

是阿底峡尊者他从印度到了西藏,他出生的地方是在孟加拉,他之后就到了西藏,

他最后也在西藏圆寂。所以,在后弘期的时候,他到西藏可以说对西藏佛法弘扬上最重要的一位大师,他在藏地的弟子也是最多的。他有几位弟子,有个叫“瑜伽士”,另外一个叫“大瑜伽士”。“大瑜伽士”是他的侍者。

During the later spread of the teachings in Tibet, the one with the greatest activity on behalf of the Buddhadharma and the broadest influence was Jowo Atisha. He had

many students, but one in particular was known as Naljorpa Chenpo [Great Yogi]. He was a fully ordained monk and served as Atisha’s attendant.

在他圆寂前,他就跟阿底峡尊者说:“您快要圆寂了,那我就会遵照您的指示,会好好去修行。”他就说:“我就会要一直去禅修,闭关实修。”他就跟尊者这样报告。

Shortly before Atisha died, Naljorpa Chenpo said to him, “After you have passed away, I’m going to practice the dharma just as you have taught. I’m going to dedicate the rest of my life to meditation.”

一般的上师听完之后,听到弟子说“会要一辈子去修持”,上师都会很高兴、很赞叹。但是阿底峡尊者没有赞叹他,甚至还对他说:“禅修是修行吗?你这样子的禅修算是佛法吗?算是修行吗?”

Usually, if someone told a lama that they would spend the rest of their life in meditation, you would expect the lama to be happy and commend them, but Atisha didn’t praise him. Instead, Atisha posed this question: “Can your meditating actually become dharma?”

那他的弟子就想:如果这个不算是佛法的话,那我还是对别人说法吧。他就想:如果我对别人讲法、说法,去弘扬佛法这样子。他就跟尊者说:“说法算是修行吗?算是佛法吗?”阿底峡尊者反问:“这样子算是佛法吗?”

Naljorpa Chenpo reflected on this: ”If meditation cannot become dharma, then perhaps I should teach others dharma. How would that be?” Atisha replied, “It’s fine to teach dharma, but will teaching dharma really become dharma?”

那弟子就说:“那到底我该怎么做才是最好的?才是佛法,才是修行。”

Confused, Naljorpa Chenpo asked, “So what is the best thing for me to do? What can I do that would actually become dharma?”

这时尊者就说:“你们所有人,就是我的所有弟子,都要依止格西敦巴。我圆寂之后,你们要依止格西敦巴为上师。”

Atisha told him, “All of you should follow Geshe Tӧnpa as your teacher.”

格西敦巴就是仲敦巴, 仲敦巴不是出家人,他是一个在家居士,但是“大瑜伽士”是个比丘。意思就是要所有的比丘弟子去依止一个居士。所以,当时他的弟子听完可能会蛮疑惑的,尊者怎么会这样说。

This was an extraordinary command because Geshe Tӧnpa [Dromtӧnpa] was a layperson and only held the lay vows, whereas Naljorpa Chenpo and many of the other students were bhikshus.接着他第二句说什么?他就说:“舍弃今生。”

Atisha gave him a second piece of advice, “You have to give up on this life.”

这是一个重点。所以,到底什么样的修持算是佛法?你如果抓到这个重点,你有舍弃今生,不贪今生的话,那么这就算是佛法,就算是在做修持。 这是一个故事。

This is the crux of whether what you are doing is dharma practice or not: if you haven’t given up on this life, nothing you do will become dharma. If you put this life out of your mind, whatever you do becomes dharma.Bamboo评论: 以前听这个故事,那时没说得那么详细。总是不明白要怎么“舍弃今生”,难道“不活了”?去自杀吗?

现在才明白,是指你修行动机的问题。

就像Bamboo做这个网站,把大宝的讲法、言行和自己的体悟都记录下来,既是自己的上课笔记,以供自己学习和复习;也或许可以给后世之人,包括自己的来生留下一些珍贵的资料,希望自己的来生看到这些 详细的修法记录,就不会像今生的前半生一样迷茫和痛苦了。

因为是做给自己的来世看的,就算资料都被删除了,也会为来生种下解脱之因。所以Bamboo不会太在乎现在这个网站有没有人看,是不是被屏蔽;或者写这些文章会不会给自己带来什么灾难还是好事,都会以平常心来做。

所以这句“舍弃今生”只是一句调整自己心态的口诀,让你外境不论是荣还是辱,都不被所转的口诀。跟前面大宝讲的那个种田的禅师,盯着远处的菩提树作为插秧的标尺其实是一样的。

第二个故事是什么呢?跟仲敦巴有关。

The second story concerned Dromtӧnpa.

阿底峡尊者圆寂之后,仲敦巴就到了热振这个地方,建立了热振寺。也就是藏传佛教噶当派的第一座寺院,就是热振寺。

After Atisha died, Dromtӧnpa went to the Reting Tsampo Valley north of Lhasa, where he founded Reting monastery, the monastery which became the seat of the Kadampa tradition.

仲敦巴在热振寺的时候,来了一个僧人,他就住在热振寺。他每天会大范围地绕这个寺院,有天就遇到了仲敦巴。

A certain monk came to stay at Reting. Each day this monk would perform the longer more-demanding outer circumambulation of the monastery. One day, while he was performing

his circumambulations, Dromtӧnpa came outside and met the monk.

仲敦巴见到这个弟子在绕寺院,就说:“你绕寺院很好,但如果你去做一个真的修持的话,会更好。”僧人就想,我不是在绕寺院,这不是修行吗?一般人的想法都是这样的。 他因为觉得这就是修行,所以才在绕寺院。但仲敦巴却跟他说:“你绕也是很好,但如果你再做一个真正的修持,会更好。” “It’s very good that you are circumambulating,” said Dromtӧnpa, “but would it not be better if you actually practised the dharma?” This seems a very strange thing to say, because many people viewcircumambulation around a sacred place as dharma practice.

他心中就开始想:“那会不会有比绕寺院更好的,或者说更有利益的修行?”他就猜想:可能是「礼拜」更好。

他就找到了热振寺里面有一个地方,就在里面开始礼拜,就像『四加行』里面「大礼拜」的方式吧。有天也被仲敦巴看到了,他在大礼拜,又对他说:“你大礼拜也很好,”但又说:“如果你能够再做更好的修持,那不是更好?”

The monk pondered Dromtӧnpa’s comment and decided that prostration must be better and more beneficialthan circumambulation. So, he found a spot within the monastery and began

prostrating all day long. “Like we do when we complete the 100,000 prostrations in the ngӧndro,” the Karmapa added. Then, one day, Dromtӧnpa came by while the monk was prostrating.

“It’s very good that you are prostrating,” said Dromtӧnpa, “but would it not be better if you actually practised the dharma?”

那个僧人一听,就更惊讶了,咦?大礼拜不是已经很好了吗?还有比这更好的吗?他想:这些大概还不是修行吧,我应该去读读经书吧!学经,去读读书。他就到热振寺找到很多经书,『甘珠尔』『丹珠尔』就开始「读经」。

一天又被仲敦巴大师看到,说的又是一样:“你读经、学经很好,但如果你去做真的修持,那不是更好?”

The monk was very puzzled. If prostration wasn’t dharma practice, what should he do instead that was dharma practice? He decided that it must be better to study the great

sacred texts, so he went to the monastery library and began reading the Kangyur and Tengyur. Then, one day, Dromtӧnpa came by and saw the monk sitting there reading.

“It’s very good that you are reading the sacred texts, said Dromtӧnpa, ”but would it not be better if you actually practised the dharma?”

这时候他就完全傻了,完全懵了。这个也不是修行,那个也不是修行,最后他想,那大概只有「禅修」,所谓的实修去吧!གོམ可以翻成「禅修」、或者「实修」。所以,他就「实修」去了。

By now, the monk was totally confused. Circumambulation wasn’t dharma practice. Prostrating wasn’t dharma practice. Reading the sacred texts wasn’t dharma practice. He decided

that the best dharma practice must be meditation, so he began to meditate, hoping that Dromtӧnpa would now commend his dharma practice.

一天又被仲敦巴看到,他就坐在那边禅修着,他就想,仲敦巴大师看到,觉得仲敦巴一定会说:他这是在很好地修行。结果仲敦巴说的还是一样,“你禅修不错,

如果再做一些更好的修行,不是更好吗?不然这样也是没什么意义的。”

And finally, one day, Dromtӧnpa passed by while the monk was meditating.

“It’s very good that you are meditating,” he said, “but would it not be better to actually practise the dharma?”

这时候他就完全不行了。因为他所有认知里面,他以为的所有的修行,他都做了,他都尝试了,但所有都被仲敦巴给打破了,他完全不知道该怎么办了。

他就请求仲敦巴告诉他:到底什么样才是修行?什么样才是佛法。不然我是完全已经懵了,完全不知道该怎么办了。仲敦巴大师怎么说呢?也是一样:“

舍弃今生、舍弃今生、舍弃今生。”说了三次“舍弃今生”。所以这个重点你知道了吗?

By this point, the monk had no idea what he was supposed to do. He had done everything he considered to be dharma practice, yet Dromtӧnpa had said categorically that they weren’t

dharma practice. The monk begged Dromtӧnpa, “Please tell me what dharma practice I should do.” And Dromtӧnpa replied, “You need to put this life out of your mind. Put this life out of your mind.

Put this life out of your mind.” He repeated it three times.

我觉得这个重点是什么呢?所谓的「修行」不是外相,不是外在的,譬如说「礼拜」啊、「读经」这些外相,重点是什么?重点是你修行的时候,你的内心是怎么想的,这是最重要的。

你在修行的每一个当下,你心中在怎么想,你怎么去理解的。如果你的想法是对的,那么你在做什么它就是修行。你「读经」它就是修行;「禅修」它就是修行。不然,如果你的想法不对,你外在在「礼拜」、「读经」,那也不是修行。

所以,是不是修行。是不是真的佛法,是看你的心,你的想法对不对。你的心有没有改变,你的心有没有利益到。

External forms are not dharma practice. The important thing is your state of mind. If your way of thinking is correct, no matter what you do, everything can become dharma practice. If your state

of mind is not correct, though there might be the external appearance of dharma practice, it is not dharma. The question is whether your practice is transformative, whether it can transform your mind, and whether it can benefit your mind or not.

就像我刚刚有提到说:「课诵」时,你可以口头上是在念「嗡嘛尼呗美吽」的念,但你心中可以在那边胡思乱想。

当你讨厌一个人,你还可以一边念,一边说:“气死我了,最好那个人去死吧!气死我了。明天希望他肚子痛,希望他拉肚子。”别人看你,哇~真了不起,你看他那么认真在念六字大明咒,了不起。但内心里,你是在诅咒别人,要他拉肚子。

甚至搞不好这个人根本不知道他在欺骗自己,他还自以为是在修行,其实他的内心根本是跟佛法无关的。这时候他在念「六字大明咒」,但是跟鹦鹉念咒是一样的。

Judging by the external appearance can be misleading. Someone chanting manis seemingly with devotion could be wishing harm on others in their minds.

大概是这样子,好,接下来休息半个小时。

Bamboo评论:2018年初,在菩提迦耶,因为大宝没回印度。Bamboo也就没参加什么“祈愿法会”,每天去正觉塔修一小时“曼达”,再读一小时藏文。 旁边有个喇嘛也在修“曼达”,但他是从早坐到晚,一两个月就修完了十万遍的。喇嘛看上去人很好,但不会任何外语,看Bamboo会说一点点藏语,就很高兴的样子。

他每天心无旁骛地修着曼达,连Bamboo都觉得他真的很精进,可堪供养。一个月后,“十万遍曼达”修完了,这时候他就不知道该干嘛了,想“读经”,但从早到晚读经也没啥意思。最后实在不知道 该干嘛才显示他在修行,他就只好又开始修“曼达”。但已经没有了任务和目标,修“曼达”也变得心不在焉了。这时候看上去Bamboo也不觉得他是个修行人了。

正觉塔是有一些组织长期供养免费食物的,还能拿到信众和法会放在你身边的金钱,如果你在那边读经、修曼达或者礼拜的话。所以Bamboo也不知道那些在正觉塔做各种修行的喇嘛到底是真的在修行还是为了这些供养。

而那个修曼达的喇嘛如果每天能分出一些时间来学点文化知识,比如英语或中文,可以跟来正觉塔的信众介绍点佛法,不是更真实的“献曼达”吗?然后他的座位铺了一层又一层的垫子,从早到晚,一天24小时,座位都一直霸着正觉塔的地盘, 难道不知道损福报这回事吗?没有巨大的福报是修不了佛法的。而这个喇嘛在Bamboo看来已经是正觉塔里这些整天坐着的出家人里最像样的一个了。

Facebook 视频